Pioneer of Computer Art and Kinetic & Light Art

Dominic Boreham’s visual art spans across a wide range of genres and mediums. He is acclaimed internationally for his pioneering use of computers, kinetics and light for making visual art in the 1970s and 80s. The innovative and iconic artworks that were made using novel technologies intersected with his knowledge of visual perception, psychology, philosophy, quantum physics and Buddhism.

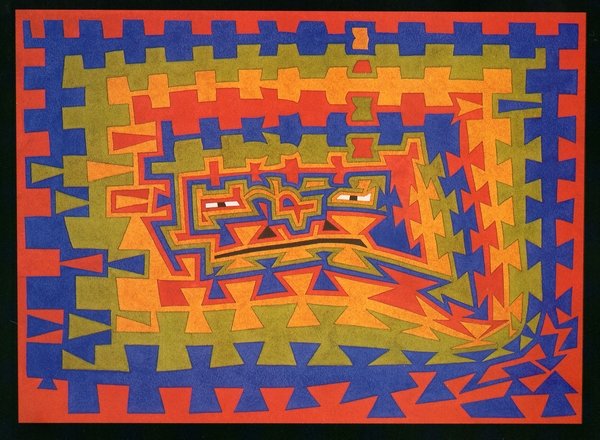

In the late-1980’s Boreham returned to painting as the most immediate and versatile medium and developed his own pictorial language of “Transactional Non-Objective Art” and “Transpysche Art”. He described his artistic development symbolically as a journey from the square to the circle; his visual art has influences of Jungian psychology, Tibetan and Zen Buddhism, Shamanism and Mythology. His work is characterised by impeccable draughtsmanship, colour sensibility, subtle depth cues, elegant strong construction, humour, spirituality, and the power of unconscious communication.

Born in 1944, Boreham lived in England and Wales until 1991 when he emigrated to France and continued creating art until he passed away in 2022.

An Obituary was published in the Guardian in early 2023.

Computer-assisted art

“Is it necessary from a a) technological point of view, (b) sociological point of view, (c) political point of view, (d) aesthetical point of view, to make a difference between an artist and a computer artist? Is it necessary to keep computer art in its own ghetto any longer?”

Dominic Boreham made innovative use of technology for creating visual art. He is internationally known for his pioneering work in computer-assisted art-drawings, which he made at the Slade School of Art, London (1977-79). The drawings were generated via FORTRAN programming and initially displayed on an oscilloscope. Later drawings were plotted on paper using a Benson flat-bed plotter and Rotring® ink pens. He plotted 15 different series of drawings; among them the STOS (Solid/Transparent Overlay Study) and IM (Interference Matrix) series are the most well-known and have been exhibited internationally.

He described the genesis and structure of the STOS series in the 1979 “PAGE42” issue, a bulletin of the Computer Arts Society (CAS). Boreham also played an important role as editor of the PAGE journal from 1979 to 1982, transforming a slim bulletin into a large quarterly journal and interacted closely with his contemporaries via CAS. Also, he toured as visiting lecturer to educate students about computer art, human vision and perception.

Interest in Boreham’s computer-assisted art continued; he was commissioned by the historian of art and technology Frank Popper to write for the LEONARDO journal in 1992, vol. 25 (“The Conceptual Framework of My Computer-Assisted Drawings: Reflections on Physics, Buddhism and Transactional Psychology”) in relation to his Indeterminacy Grid and IM series.

He was awarded Ph.D. in 1983 for his doctoral research in pictorial structure and artificial vision, which was jointly conducted at the Royal College of Art, London and the Leicester Polytechnic, UK. Boreham did pioneering work using a prototype raster graphics system to make coloured digital paintings and worked on developing image analysis and extraction techniques at the Leicester Polytechnic “Human Computer Research Interface Unit”.

Boreham’s computer-assisted art-drawings are in various private and public collections; they have been exhibited widely over the years and continue to be exhibited, see: Exhibitions Page

Kinetic and Light art

Boreham did his B.A. degree course (1974-1977) at the Wimbledon School of Art, London, where he made innovative use of kinetics and light for his visual art. His installations are in casings in wood and Perspex structures that enclose his self-made electronic programmers to modulate light in artist designs.

Two of his kinetic art works from Wimbledon, the “Rainbow Bird” and “A Planet for Kandinsky” were generated by refracted optical light projections. In these beautiful and extraordinary works of art, one finds a whole spectrum of marvellous coloured light that transport the viewer to higher dimensions.

The “Yantra” is an electronic installation within a large square, slim and black-painted wooden structure, that generates the Yantra using multiple light projections in a series within a cycle. The range of cool glowing colours of the Yantra change gradually over a cycle that repeats while the installation is running.

Boreham also made a circular installation “Ranismala” for the Buddhist Vihara, which radiates a diffuse white light in a halo behind a Buddha Statue. There are several artworks from this period that utilise polarisation of light in “compositions on four planes” and “compositions in a mirror cube” in a constructivist style. While doing his degree course in Wimbledon, Boreham studied Theravada Buddhism under the Venerable K. Piyatissa Thera at the London Buddhist Vihara. His regular visits to the Vihara were the beginning of a life-long interest in Buddhist psychology and philosophy. We see the Buddhist influences in Boreham’s Yantra and Ranismala, which in fact have western constructivist design.

Boreham’s achievements at Wimbledon were well recognised; he was awarded first prizes for Graphic Art and Painting, and the student union prize for the Best Work in the Annual Exhibition during his B.A. Degree course.

Innovator of Transactional Non-objective Art and Transpsyche Art

Watercolours

Throughout his long and disparate search for a pictorial language that had an empirical universal basis, rather than merely a personal style, which he rejected from the beginning, Boreham’s study of the psycho-physical characteristics of perception gradually evolved, through rigorous experimentation into complex structures with different colour combinations and a variety of motifs.

In his watercolours from 1984-2000, Boreham explored specific hues until a final combination was determined. In 2000 Black/Payne’s Grey begins to be used more to set the coloured forms in a void (background). Five years later (2005) colours begin to be grouped: Cold-Hot; Light-Dark; Advancing-Receding; which divide the picture plane into regions and introduce more effects of 3D.

Boreham uses ambiguity at different levels between: Representation and Abstraction; Figure and Ground. There are contradictory 3D Cues; uncertainty of clear boundaries between a figure and its environment, and interconnectedness of everything. Furthermore, the Titles leave much to the viewer.

A variety of motifs are used in Boreham’s paintings and drawings, such as: Labyrinth; Tree; Triangular Arch, nested; Pavilion, Temple; Bird; Face; Eyes; Egg-shaped oval; Interlocking shapes; Stretched shapes; Parallel lines and Mirrored lines. Specific motifs appear at different periods of his art; some that are used earlier on are not evident in later works.

In the development of his pictorial language with an empirical universal basis, Boreham employs his knowledge of visual perception and psychology, his spiritually springing from Buddhist meditation practice and his conviction of tapping into the collective unconscious/psyche. His watercolours and drawings challenge the viewers to break away from the everyday notions of reality and search deeper to find a way of being that is less conditioned.

Drawings

It is in the drawings, where we are no longer mesmerised by the exquisite colour of the paintings, that we are made aware of Dominic Boreham’s impeccable line. Very early on he had taken to heart Klee’s dictum of “going for a walk with a line”, later to be supplemented by Ben Nicholson’s comment that Klee’s going for a walk with a line was too pedestrian for his taste and he preferred “flying with a line”.

Boreham raises the line to total independence as the principle pictorial element, freed from its shackles of subordination to figurative description. Further, he adopted the line in the form of an arc as the fundamental element. Firstly, because in Nature the arc predominates, but the straight line is almost absent. Secondly, in the act of drawing, the arc is the most natural movement for the human arm. And this arc is always to be perfect, not shaky, not dithering, but also not governed by rigid geometric curvature. It is also required to be at all times, in all places elegant.

In a drawing the first line is joined by the next which must be in total harmony with first, creating a continuous flow and rhythm of lines. The lines are elegant, sophisticated, impeccable, balanced, in harmony, dancing together in cosmic rhythm in unexpected ways. Where forms and the spaces between them, which often connect, transforming figure into ground, are all of equal import.

The viewer becomes transfixed by the beautiful complexity, spirituality and humour in Boreham’s drawings that leave a deep impression on the psyche. With admiration, we return to the drawings, searching for the hidden meanings behind the enigmatic titles.

“I describe my artistic development as a journey from the square to the circle, where the square symbolises rationality and logical structure, Western science and philosphy. The circle, on the other hand, symbolises wisdom, holistic awareness, Eastern mysticism and eternity. ”